Why Adrenal Fatigue May Be a Misnomer

A recurrent topic in the alternative health world is adrenal fatigue. In school, we’re constantly being reminded that chronic stress is likely contributing to patients’ health— and in a big way.

This is definitely true. Chronic stress does eventually end up influencing adrenal function.

But to me, “adrenal fatigue” implies that there’s something physiologically wrong with the adrenal glands. Like they just can’t keep up with the amount of stress they’re under. However, this may not necessarily be the case.

What’s An Adrenal Gland?

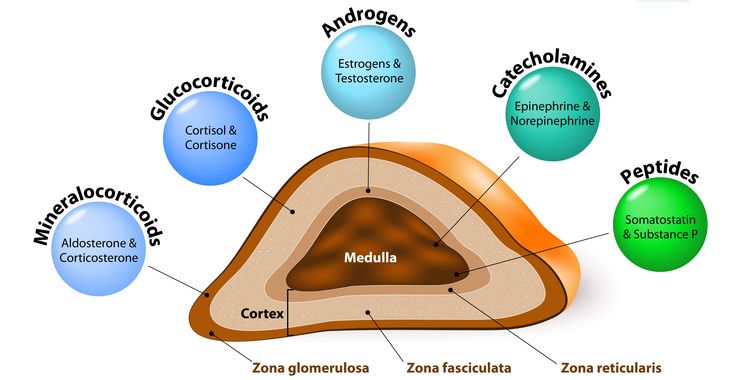

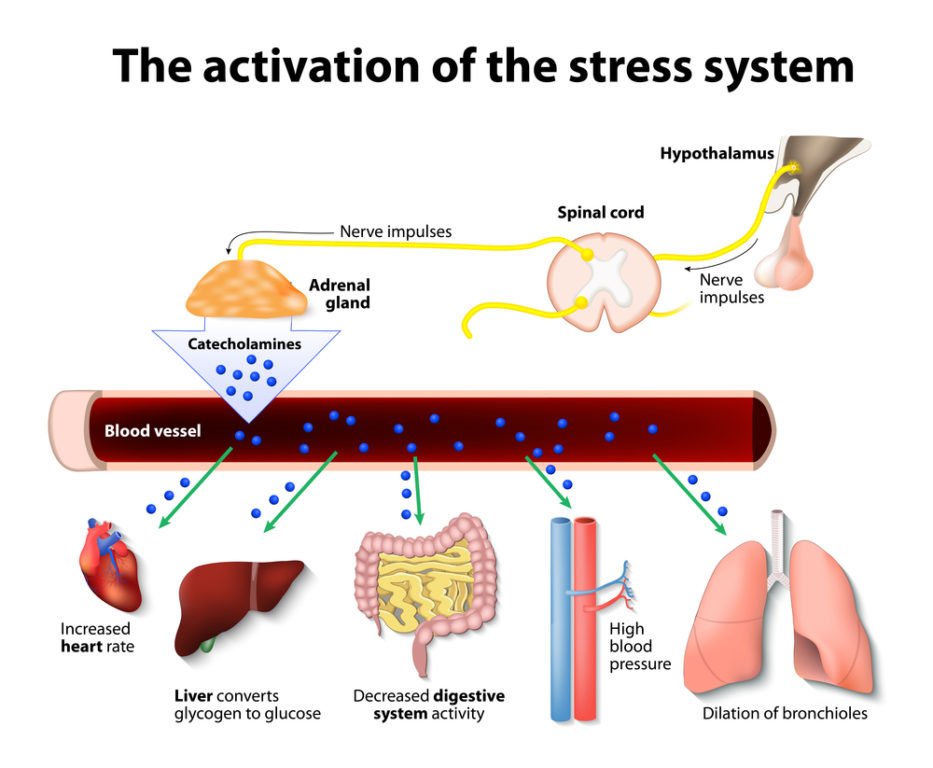

If you don’t know, the adrenals are two pyramid-shaped glands sitting on top of your kidneys. They’re in charge of secreting glucocorticoids and catecholamines like epinephrine to activate your sympathetic nervous system. This activation is more commonly known as the “fight or flight” response.

The most famous (or infamous) glucocorticoid is cortisol. Cortisol is a steroid hormone that’s the desired end-product of activating fight or flight in response to a stressor.

Not All Stress is Bad

In the short term, cortisol and other stress hormones are necessary to help your body deal with whatever stressor has disturbed your homeostasis. It does so by activating your sympathetic nervous system, raising your blood sugar, and putting a halt on things like digestion, which isn’t crucial during a stressful experience.

We need stress. Evolutionarily, we needed our stress response to combat real, life-threatening events like being chased by a tiger or starvation. Stress is what helps us adapt to our surroundings.

We still need stress, even without threats of tiger attacks. Activating the stress response helps increase our motivation and energy in times of need, like when we give presentations, have an important meeting, or take final exams.

Unfortunately, modern stress takes a much different form than evolutionary stress.

Oftentimes, our animal brain can’t interpret the difference between a tiger attack and getting up to give a presentation or even getting stuck in a traffic jam. So when you add up all of the stressors we encounter during a typical day in the modern world, you might start to see the problem. Your brain may actually think you’re being attacked by at least 10 different tigers in one day.

Chronic Stress and the HPA axis

It’s the chronic nature and frequency of stress that causes the problems we associate with adrenal fatigue. And this has a lot to do with other neural structures (besides the adrenal glands) that are involved in activating fight or flight and cortisol release.

The adrenal glands are the final target for our hormones when we’re stressed. Whether it be physiological, mental, or emotional stress, the same cascade activates our sympathetic nervous system with every deviation from homeostasis in the body.

The neural system in charge of activating this stress response is referred to as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, or HPA axis for short.

When your body senses a stressor, the hypothalamus (a structure in the brain) secretes a hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which tells the pituitary gland (another structure in the brain) to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH then travels through your blood to stimulate the adrenal glands, which produce and release cortisol.

With acute stress, cortisol rises and gets you through the rough time, simultaneously telling the hypothalamus and pituitary that they’ve done their job and can stop secreting CRH and ACTH.

With chronic stress, the hypothalamus is constantly being stimulated to activate the stress cascade by releasing CRH, despite the high levels of cortisol. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland become desensitized to cortisol, and the feedback from cortisol gets less and less effective at turning off the stress response.

Prolonged activation of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland can eventually lead to the adrenal glands being unable to regulate themselves due to an exhausted hypothalamus and/or pituitary.

Adrenal Fatigue Begins in the Brain

So as you can begin see, it may not actually be your adrenal glands that are fatiguing. It’s likely your brain! The problem is the perpetual activation of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, leading to chronically high levels of cortisol that screw up the natural rhythm of cortisol secretion.

And it’s not necessarily true that your cortisol secretion is just steadily decreasing to zero. The key word here is cortisol dysregulation— sometimes your cortisol is high when it’s supposed to be low or low when it’s supposed to be high. This would explain your being exhausted in the morning and wired and tired at night.

The Correct Diagnosis Dictates Correct Treatment

My traditional Chinese medicine instructor always says, “If your diagnosis leads to incorrect treatment, you will be marked incorrect.”

Obviously this is only relevant for testing purposes and not real-life diagnosis. But it sheds light on the importance of the diagnosis in dictating an effective treatment.

In the case of adrenal fatigue, if we only treat the adrenals, as the name implies, we miss the important root of the problem— the perpetual activation of the hypothalamus and pituitary. This can really derail the treatment approach. A more appropriate name for adrenal fatigue may be HPA axis dysregulation, as described by Chris Kresser, L.Ac, a prominent ancestral health expert.

I will be exploring ways to influence your brain’s response to stress rather than just the adrenal response in a future post. I will also be looking into adaptogenic herbs that are believed to modulate the response to stress by interacting with the HPA axis. Stay tuned!